Deserted Island DevOps Postmortem

In my experience, it’s the ideas that you don’t expect to work that really take off. When I registered a domain name a month ago for Deserted Island DevOps, I can say pretty confidently that I didn’t expect it to turn into an event with over 8500 viewers. Now that we’re on the other side of it, I figured I should write the story about how it came to be, how I produced it, and talk about some things that went well and some things we could have done better.

Popular lore now holds that the above tweet (1/1/25: tweet deleted as I deleted my Twitter account) was the genesis of Deserted Island DevOps, but I’d actually suggest that it was a Slack conversation I participated in at the end of February. The COVID-19 pandemic was ramping up, event cancellations were starting to compound, and an internal conversation was brewing around virtual events. With my usual confidence, I predicted that it wouldn’t be possible to put together a successful virtual event in a month. I’m willing to admit at this point that I was wrong on that one -- turns out, with sufficient hustle and a keynote speaker with nearly fifty thousand Twitter followers, you can do a lot of things. While Deserted Island DevOps was a wild success, I would be remiss to not point out events such as Gremlin’s Failover Conf and Lead Dev Live who both have run incredibly successful and well-produced virtual events on a short schedule.

Why did I think you couldn’t pull it off? Well, let’s put a finer point on it and ask a bigger question -- why do these events exist? Why do companies pay tens of thousands of dollars to exhibit at them? Lead generation! Everything exists to serve the almighty MQL funnel. An in-person event is an opportunity to scan badges in exchange for a t-shirt or a stress ball or some other piece of swag, and those scans convert to a data point on some KPI dashboard that rolls up to a VP of Marketing, and the theory goes that some percentage of those scans result in someone opening an e-mail for a reason other than to click ‘unsubscribe’, and some percentage of those people will click a link to a whitepaper or get a demo of your product or service, and some percentage of those people will eventually buy something from you. In a virtual event, it remains to be seen if this basic calculus applies. How valuable, exactly, is the human interaction you have at a booth in terms of you eventually opening that email? Do you feel compelled to sign up for a demo just because you got a t-shirt? We don’t really have the data to say one way or another at this point, but my grander thesis is beyond lead capture the real thing a sponsor buys at an event (and the thing that you sell, as an attendee) is attention. When you’re trapped along with thousands of other souls on the show floor at a tech conference, your senses are under constant assault by a concentrated stream of capitalism. The “brand awareness” that a booth or sponsorship can generate is extremely high - what else are you going to pay attention to while you’re there? Even the coffee and pastries are sponsored by someone. The lanyard around your neck is probably branded!

Let’s compare this to a virtual event. You don’t have to watch the talks, or the interstitial segments. You can jump in for a talk and leave easily. Maybe you leave the Zoom (or Zoom-shaped object) on in the background, muted, during talks you don’t care about in order to browse the internet or keep doing work. Your attention is not present in the same way that it is at an actual show. That said, there’s a lot of questions we don’t have answers for yet - when you do pay attention, is that attention worth more, or less? Are you more engaged when you’re not physically “there”? Does the setting matter? I believe that it does on some level - any successful event will have an ethereality to it, something that takes you out of space and time and places you in a constructed moment (or in the work of Cartier-Bresson, a “decisive moment”) that cements you in a world that is not your own. A chance meeting in a hallway over coffee or drinks, reconnecting with an old friend or acquaintance, a story shared that resonates just so - these moments, I believe, are what keeps us gathering for these events. How could you possibly replicate these moments when you only have a chat channel, a video feed, and the endless hellish screeching of our modern reality playing out in a Twitter feed or on CNN out of the corner of your eye?

So, yeah, I mostly decided to do this as a bit. As COVID-19 spread, and travel ceased, and offices emptied, I quickly pitched a format change for the on-again, off-again podcast I’d been hosting for the past year into a once (then thrice) weekly live stream on twitch.tv. My thought process was “well, people are stuck inside, they’re gonna want to watch something, and I have all this A/V junk…”, so you know, why not go for it? My colleague and co-conspirator Katy was game to ride as co-host, so off we went into the wild world of extremely minor Twitch stardom. I got a crash course in many of the more technical aspects of streaming - I knew a bit about OBS (Open Broadcaster Software) and other production tasks, but the best way to really learn more is by doing, so I did -- a lot. Throughout March, these streams helped build up not only our ability to technically produce live content, but also our rapport as co-workers. In the interest of not being boring, and because we both liked playing video games, we streamed video games on Fridays. Why not? One of our first game streams was Animal Crossing: New Horizons, and we both became enchanted with it. The art, the design, the whole package immediately captured our interest -- along with pretty much every other developer advocate I know.

By the end of March, it was clear that we were in for the long haul with our terrifying “new normal”, and ideas were percolating. I noticed that several twitch streamers had started to create and run special events on their Animal Crossing islands -- casinos, game shows, things like that. I also had recently found a pattern in the game that let me build a stall, and apply a custom design to it - so I put the Lightstep logo on there and made it look like a chintzy trade show booth (complete with swag to give away!), took a screenshot, and tweeted it out. Tom McLaughlin replied “We should hold a conference in animal crossing.” and… well, that kinda counts as validation, right? At least two people replied to his reply, and before you know it I had a catchy name and what I felt was overwhelming support for the idea. One trip to Namecheap and some time in Photoshop later, we had a website and a (extremely) rough mockup.

In all honesty, launching the page on April 1st was a bit of a hedge. If it flopped, then I could play it off as an April Fool’s joke. Instead, I had over a hundred registrations on the first day - for a conference with no announced speakers, no sponsors, and no actual idea of how to make it all work other than a vague “well, you can put things over things in OBS…” sense. At that point, I felt pretty locked-in, and started planning in earnest. Reader, I wish I could tell you that I exhaustively researched and consulted with experts in the space, but that would be a lie. I mostly went off my gut feelings and the spirit of events that I respected. I’ve been a huge fan of the DevOpsDays format and ethos - no vendor pitches, focus on community, let the speakers shine - and so I committed that this should be that. From the start, I resolved that registrations wouldn’t be shared with sponsors (or anyone else), and that I wouldn’t take a dime from anyone that wasn’t already paying me for my time. I didn’t feel like it’d be in the spirit of the event to monetize it in any way, really. After throwing together a call for proposals on Sessionize, I sat back and let the magic of the internet take hold - well, I also tweeted about it a lot and bugged a few people in person to submit talks. Katy and I formed the program committee, reviewing talks for inclusion. It was harder than expected to build a slate - there were over twice as many talks submitted as we had room for (even after expanding the speaker lineup; originally I had envisioned only 8 speakers, but we pushed it to 10) and they were all exceptionally good proposals.

Meanwhile, the world continued to turn, and I started to figure out how exactly this whole thing would fit together from a technical and organizational standpoint, and how to build a set inside Animal Crossing. Originally I had conceived of using an actual in-game prop as the backdrop to overlay slides against, but this proved to be unwieldy and ineffective for actually viewing what was on the slides. In addition, I quickly realized that the camera - while good at displaying my character in-game - wasn’t really suitable for the sort of camera work you’d want to do in producing an event. The default camera centers on your character in the game world, and even worse, when you’re not in your house it’s fixed on a plane facing north (so you can’t rotate it around you). There is an in-game camera feature that gives you more options (like pan, tilt, and zoom) but it introduces several visual overlays that can’t be disabled. I also had to consider, quite unexpectedly, the prospect of rain. Animal Crossing has seasonal weather, and in the spring, it rains a lot - what if it rained on the day of the event? I could “time travel” as its referred to by the AC community (adjusting the system clock of the Nintendo Switch to move to an arbitrary season and time of day) but this would introduce additional complications to already tightly scheduled logistics. These aren’t the only challenges in-game, but it’s worth noting that challenges were there. These challenges, though, were part of the charm of the event I believe. Limitations can drive creativity. This is especially true in software - the stories we remember and talk about are usually the ones where we had to overcome limitations in some creative way.

These challenges lead to several conclusions on my part. First, I’d need to hold the event inside my house, rather than outdoors. This opened up flexibility in camerawork - indoors, you can rotate the camera 360 degrees around a fixed point - and in set decoration and design. In order to have a large enough space, though, to fit everyone I’d need a bigger room… which meant I need to acquire about 2 million bells (in-game currency) to pay for those expansions and various furnishings (such as the podium, and the TV) needed to bring the vision together. The exact details of how I came about the in-game money aren’t really germane (there’s a system known as the ‘stalk market’ where you can buy and sell turnips; buy low, find an island online with high prices, travel there and sell them) but I did get to play Animal Crossing for my job which was kinda neat.

The second major piece of the puzzle was actually producing the whole thing. Virtual events offer a greater flexibility when it comes to how presentations are actually delivered compared to an in-person venue, of course, and what I’ve seen is an increasing reliance on pre-recorded talks. From the onset of planning for Deserted Island DevOps, I made a conscious decision to not rely on them -- despite the multiple nightmares I had leading up to the event about internet connections dropping out and speakers or viewers being left in limbo -- because I believe that a huge part of speaking is real-time feedback. Normally, you’d get this feedback from watching your audience. Are they paying attention? Nodding? Laughing at the jokes? This is one of the elements that I’ve found lacking in webinars and other virtual event tools. Indeed, they seem designed to remove you, the speaker, from the audience as much as possible. Zoom Webinar, GoToWebinar, etc. all remove audience cameras entirely from the screen, and hide chat away for the most part. It’s intended that you use narrow, purpose-built tools like Q&A features in order for questions to be collected and responded to. This, to me, feels like a huge departure from the way I like to talk to people that I find it difficult to be enthusiastic about. While I was planning on streaming to Twitch anyway, I believed that this decision would reinforce the value of live talks anyway, as Twitch has a convenient chat feature that’s integrated into the viewing experience both culturally and technically (the chat window, after all, is right there next to the video player. It invites you to participate), thus allowing speakers to get real-time encouragement and questions. In addition, I hoped having multiple speakers in a Zoom call (with some speaking, and some listening and reacting on the island) would give speakers a virtual audience they could speak to and address as humans. I’m happy to note this worked extremely well -- all the speakers loved it, so I’d recommend it to anyone trying to run their own virtual event. On that same note, I’ve had people who are in a more professional events marketing role ask me about the choice of platforms… I honestly think you should use what you have, and Twitch is a fantastic platform for live-streaming video. It handles scale flawlessly and seamlessly, you can provide closed captions, chat moderation is fairly straightforward. I’d like to see a version of Twitch that maybe is aimed at a more midmarket audience -- like, I get it because I like watching people play video games, but I understand that the srs business crew might not be down with it, I dunno. I also believe that the events success can be traced, in large part, to the fact that the content wasn’t gated. You didn’t have to download an app, or log in, or sell your soul to watch the stream. You clicked a link, and it worked. This drove a lot of traffic organically, as well - while our concurrent viewer count never quite hit 1k (goals for next time, I suppose), we had over 8500 unique views and over 11k views total so we had a pretty constant stream of people coming through and a decent amount that were there the entire day. The discoverability of Twitch also made this interesting - we had enough viewers to be within the top ten live channels for our category the entire day, the best I saw us do was number three overall, but that’s pretty impressive for a DevOps conference. In a more general sense, I think things like this should be accessible in general. Information wants to be free, y’know? Did we inspire someone, stuck at home, to something greater? Did someone watch this and think “huh, this could be an interesting career?” I don’t know, but I hope that we inspired people in some small way.

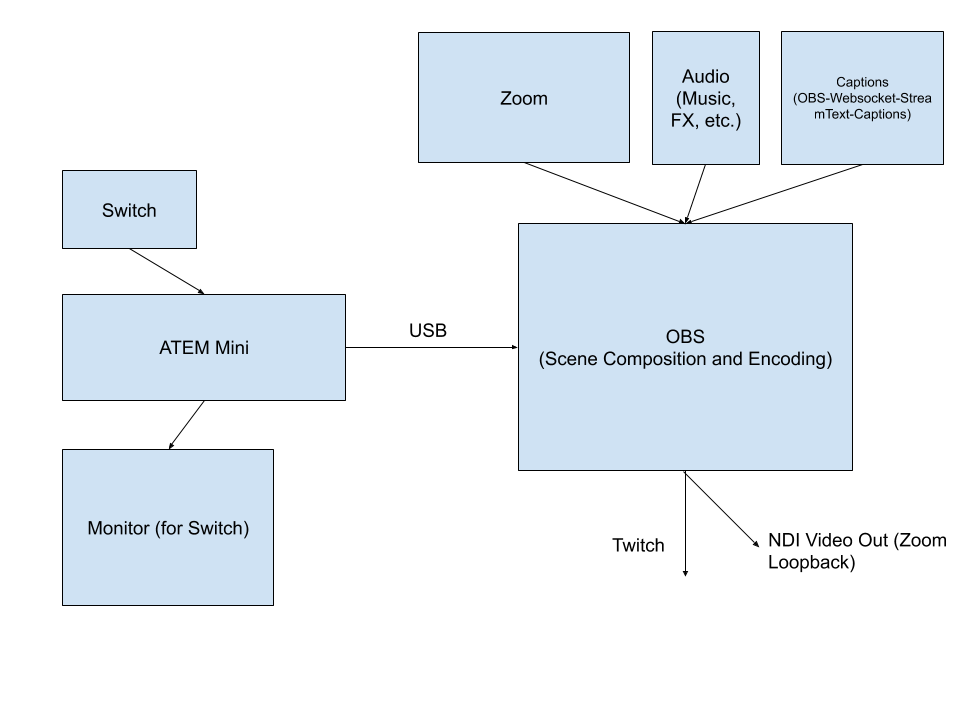

With a rough idea of the “how”, I turned to making solutions. The actual technical aspect of production was pretty straightforward, as I mentioned earlier. A pretty quick drawing of it follows, but I’ll explain it in more detail.

I use a Blackmagic ATEM Mini to capture HDMI video sources and send them to my computer - this is what drives the Sony DSLR I use as a webcam, but it can accept 4 separate HDMI inputs. It also offers convenient keying functionality on the unit itself, making it handy to take on the road for recording trainings, meetings, whatever. I originally planned to use it for my OPS Live! event at the Observability Practitioners Summit at KubeCon NA 2019, but it didn’t arrive in time, but I repurposed it as part of my home studio. Since Deserted Island DevOps didn’t involve any multi-source switching or compositing, it basically got to act as a fancy capture device for the Switch. The ATEM Mini is hooked up to a second monitor, that I used to watch the raw gameplay output from the Switch. ATEM acts as a video source when connected to a PC or MacOS computer, so I was able to easily add it to OBS.

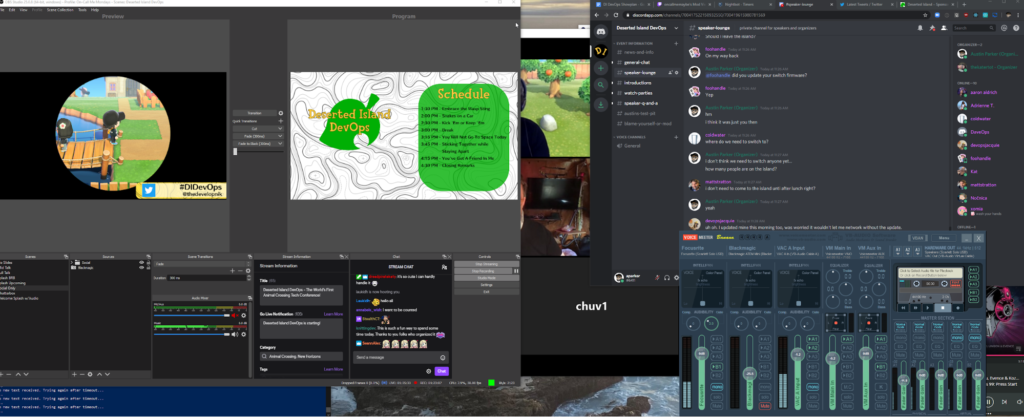

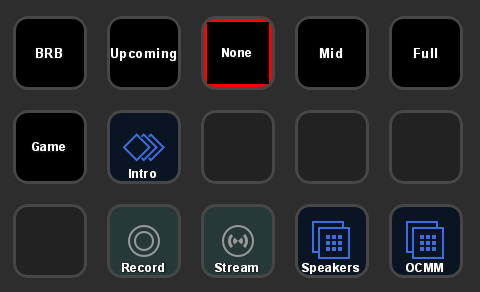

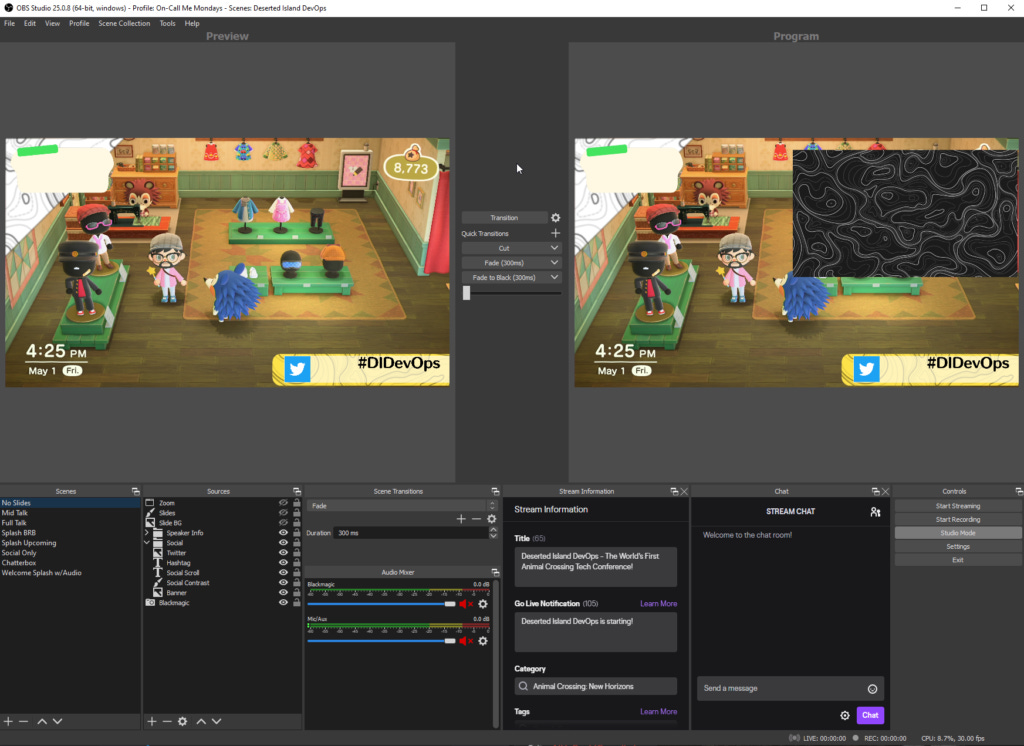

A complete breakdown of what you can do in OBS would be beyond my ability or desire to detail in this piece, but this is basically what I stared at all day. Each overlay was broken down into a specific OBS scene, which I controlled through an Elgato Stream Deck -- a convenient little piece of kit that gives you 15 physical buttons that can be mapped to various actions, like ‘switch scene’ or ‘start recording’. The Stream Deck was a huge convenience, since I could easily flip between the slides taking up a corner or full screen with one press of a button without having to click around in OBS. This was rather valuable, as I needed to split my focus a few different directions while producing - I kept my Switch controller nearby so I could adjust the in-game camera as presenters moved around during talks, while switching between scenes with the Stream Deck, while clicking between the Twitch chat mod view, various Discord channels, Twitter, the show plan in Google Docs, and so forth. I also kept a notebook next to me with big handwritten notes like “REMEMBER TO RECORD” and “MY MIC IS ON A2 IN VOICEMEETER”.

A fancy audio routing trick with Voicemeeter and OBS let me talk to the Zoom call without my audio being routed out to Twitch, so we could effectively communicate (at least one-way) about switching slides and so forth. I’d ask the next presenter to share their screen, go into OBS and modify the crop filter on the Zoom source (because everyone’s slides were a little bit different…) and resize everything just so. One fun trick - you might notice that I don’t have separate scenes for each speaker. That’s because all of the text for the stream graphics (speaker, talk title, etc.) was actually stored in a file. Stream Deck macros allowed me to switch between speakers with a press of a button, by overwriting the text in several files which OBS would then load. This saved a lot of time in creating assets, since I only had to create them once rather than for each speaker separately.

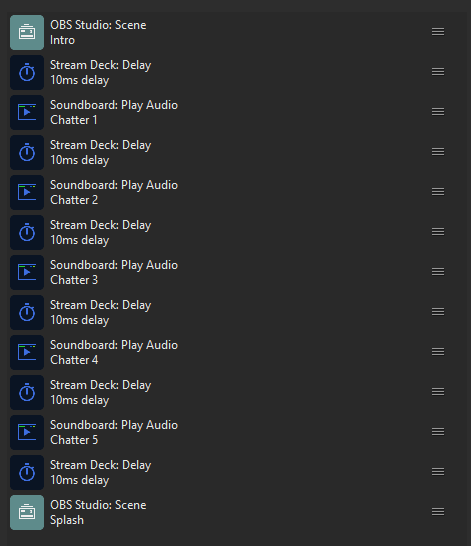

Since I was already pretty deep into running things live, how did I make the intro? That was some special Blender stuff, right? Well, no. Since I already had the text box as a vector, I exported it as an SVG, made a web page, and added some JavaScript to mimic the ‘typewriter’ effect of how text appears in Animal Crossing. I (painstakingly) added in the animalese sound effects and synced them up through another stream deck macro but literally as I write this I realize I could have just imported it into my local web site and probably synced it up that way. Note for the future, I guess. (Those ‘10ms’ delays aren’t actually all 10ms, I just got lazy with the labels). The pictures overlaying the welcome screen at the end were created by me making a bunch of different images with a new screenshot each time, and turning them into an OBS slideshow. OBS lets you start a media source as you transition into a scene, so adding in the ACNH theme was as simple as ripping it from YouTube into a mp3 (thanks, youtube-dl!) and adding it as a media source to the ‘Welcome’ scene. The macro took care of the rest! I also used it to make the short promo gif that I posted to Twitter, but with different source text. OBS has a ‘Browser Source’ that you can load any URL into, even a local one, so I simply imported the HTML file into OBS through that and we were off to the races. Fun side note 2 - I couldn’t convert the ripped TT font that I was using into a webfont, but css dont care - you can give it the path to a local truetype font and it’ll load it no problemo.

There’s a lot of things I’d do differently if I did this again - I’m not sure if I’d use OBS, for one. While it’s free and effective, there’s some pretty basic features that it lacks - snap-to-grid for elements, foremost amongst them. It also has very limited options in terms of text overlays; You can create some basic ones, and source the text from a file, and even make the text scroll… but that’s about it. I know other tools exist like Wirecast from Telestream, and maybe I’ll look at that since I already have a license, but we’ll see. xSplit is another I’m aware of. I wanted to add in something like an overlay to display tweets or twitch chat, but I found the options kinda frustrating to deal with on a short amount of time (realistically, I only spent a week working on the production prep side of things, not that long in all) so I went with what I had.

Behind the scenes, there’s a lot that happened as well. We recruited - last minute, somewhat - a small team of moderators. I made the decision about a week out to create a Discord server for the event, based on concerns we had about both moderating Twitch chat and the fact that it would be difficult to reliably get questions and answers done in there. I thought about a Slack for a minute, but I’m already in a million Slacks and hate most of them. Even the name frustrates me. It was cool when the other option was Hipchat, but now that it’s the Enterprise Communication Tool Of Choice it just reminds me of a pair of Dockers, which is actually kinda ironic. That said, when your competition goes by ‘Meet’ and ‘Teams’ I guess you kinda win by default. Katy was invaluable in helping source moderators from the early adopters of our Discord, who we quickly (as in, like, a day before) empowered to keep both the Discord and the Twitch chat clear of nuisances. I also configured a Twitch bot (Nightbot) to automatically moderate the chat, adding in a plethora of bad words and other restrictions on spamming, caps lock, emote spam, etc. It was tuned a bit too tight at first -- and honestly, maybe a bit too tight overall, because it timed out a bunch of people when the first talk ended… but, that’s a learning going forward. Setting the chat to followers-only on Twitch worked well, though - I probably overfitted for reducing the amount of human moderation we’d need to do by being too aggressive on automatic moderation and limiting things, but I was somewhat worried about the worst of the internet showing up, especially if the event went viral(er). It was nice to see that not happen! Our Discord and Twitch, for the most part, were well-behaved and polite and convivial. The watch parties that spawned out of the Discord were also absolutely delightful to see - people shared screenshots of themselves hanging out on other attendees islands, usually with some sort of ‘viewing space’ set up. We were also able to quickly make adjustments as needed - we added new channels as the event was going on in order to keep the main chat more clear (a ‘hallway track’ channel for discussing the current talk became very popular), and most crucially the entire experience of onboarding to Discord was completely self-serve. Our Twitch bot would mention the Discord invite link every 15 minutes (or on demand through a command), allowing people to join and get involved. Moderators and the host could look through the Q&A channel in order to find questions to ask live, and speakers could head there afterward to have more in-depth conversations. Overall I think the entire chat experience went really well.

Another important part of the experience was our captioning. This part was pretty easy, or at least pretty hands-off. I asked other event (in-person and virtual) organizers about what captioning tools they use once I realized that machine translation was going to be utter trash, and found White Coat Captioning through that. The actual mechanics of it were extremely straightforward - the captioner sat in the zoom call and… well, transcribed what people were saying. They used a service called StreamText to send the captions out to a website, that I was also able to pull caption data from using an OBS plugin. This plugin sent the captions to OBS, which encoded them and sent them to Twitch along with the video feed. We got the captions afterwards, so I can add them to the chapterized video on YouTube. This was 100% worth it, and I think every virtual event should follow suit (also in-person events!)

Let’s see… laundry list time, because I’m tired of making this narrative. Things that worked, and things that didn’t, and things that just irritated me.

- Nintendo, I would really be happy if I could turn off the overlay on the camera mode. The little viewfinder frame tics bug me so much, and they were impossible to completely hide.

- One of our speakers had an interactive segment. I thought it was just a poll, so didn’t mention it during prep, but it turns out it also had an interactive “write whatever” part.. Props to the community for rapidly downvoting some of the racism but it was on stream for a little bit, so I’ll have to clip that out of the final uploads. Be sure to check this sort of stuff in the future!

- There’s a lot of things I didn’t think about until I needed them. Stuff like social cards to promote talks and speakers and the show, a press kit, etc. etc. Would be good to have that ready in the future.

- Crap! I forgot to have everyone throw out party poppers at the end. In addition, there’s probably a hundred little ideas I had that didn’t happen because I forgot to write them down.

- I think the registration process was a bit lacking, but I was optimizing for easy and non-invasive over anything else. That said, there’s a couple of little things that would have been nice that I didn’t do, like having links to the Discord on the confirmation page.

- In terms of polish, I wish there was a way in Zoom to have fancier audio routing. I was able to keep myself muted and talk into the Zoom call to cue people up, but I everyone else talking on it could be heard all the time. This wasn’t a huge issue, but it would be nice to have something where the host audio independent of the rest of the Zoom participants. I dunno, I think you could do this by having a Zoom call + Discord call going to different virtual audio cables, then mute those at the appropriate times? Something to investigate more.

- The color grading for the output seemed pretty bad… like, the white balance was off somehow? I’m not really sure how much of it was simply Twitch compressing things on my end. Screenshots that I saw seemed mostly fine.

- It would have been nice to have two cameras in-game, but that takes a slot away from a person. I was really trying to make sure we didn’t have to do a lot of getting people in or out of the island except for breaks, so I wanted to maximize the number of actual participants that could be in game simultaneously. I do think that we did a great job here - there was only one accidental disconnect, and it was going into a break anyway, so it didn’t really mess things up much.

- Some people have asked why the event started at 10 AM ET… well, I live on the east coast, so that’s a convenient time for me. It wasn’t just that - I wanted a time that was convenient for western europe as well, so I figured might as well split the difference.

All in all, I think it went extremely well - better than I had anticipated, certainly. We’ve had writeups in TechRepublic, Vice, TechCrunch, and VentureBeat so I’ve certainly given the content mill some grist for 15 minutes (and what greater honor than that, in tyool 2020?) The live event had 11,825 live views with 8,582 unique viewers and as of this writing, another 1556 views of the full video. By the time this goes up, the talk videos will have also gone up on YouTube, so we’ll see how those do.

Stepping back, I wonder what’s next? I enjoyed doing this, maybe we’ll do it again later this year, but I’m not sure. I think there’s going to be a wave of people trying to do similar things, some of which will probably be better produced, better funded, whatever - the ideas are free, I’ll be interested to see what happens. In a longer term sense, I’m a fan of the idea that we use games as a social space to bring people together in the way that physical events do, and I’m pretty convinced that we’re going to need something that isn’t just endless Zoom webinars for event spaces. This obviously isn’t a new notion - I mean, Second Life has been a thing forever (who can forget that brief moment in the 2008 US Presidential election when Newt Gingrich held town halls in SL?), there’s newer platforms like VRChat or Altspace… I think the thing that makes AC work is its simplicity. In better times, a Switch and a copy of ACNH is a pretty small investment to make, compared to a VR rig, but more importantly than that it’s that ACNH is just… simple. You don’t need to be an expert at much of anything to move around, to dress up, to interact in ACNH. You just kinda do things, and its cute. Like I said earlier, limitations can be helpful - limitations can also be valuable. One of our speakers wore a tiny crown (which costs like a million bells or whatever, it’s an expensive fashion item) and Twitch chat started popping off - why? Well, because if you play AC, you know what that thing is worth, you know its a status symbol. Completely freeform platforms don’t really have that same sort of cachet. Like it or not, human social interaction comes with a lot of subtle clues and markers that infinitely expressive platforms can’t replicate, simply because they’re infinitely expressive. You need a smaller set of defined ‘rules’ about your platform that are easy for people to grasp and to know. I think this is somewhat important to providing a convincing proxy of real events, because it provides a way for us to be expressive and for that expressiveness to be approachable. Let’s ignore, for a moment, that it also reflects existing inequities in some way, that’s a blog for another time.

What I’m most proud about, though, is the community that formed around this event. I think that, in and of itself, is enough reason to keep trying to push forward and keep doing these kind of events in the future. Everyone came as a stranger, but left as a friend, and in our increasingly uncomfortable world, a new friend is pretty valuable indeed.

I hope this answers your burning questions about how this whole thing worked. If you've got more, feel free to bug me on Twitter! Want to watch the talks? They're in this playlist on YouTube.